Lough Hyne Loop Walk

From the car park, walk back out to the road. Go left on the road, which starts to swing right, upwards – ignore the lesser level road going out left along Lough Hyne. Continue up your rather steep winding road, watching for traffic.

Lough Hyne Loop

Overview: 7km /1.5Hrs

Terrain: Quiet roads, steep here and there.

Start and finish: Lough Hyne

At the top, turn left at a T-junction with a ‘Skibbereen 8miles’ sign, and then left again at the next T-Junction about 300m later. After another uphill 500m, watch for a fine ringfort on your right, just at the crest of the hill. This quiet road wanders along, generally southeastwards, with Barloge Hill on the left and improving sea views to the right over Roaring water Bay, and you should see over to Mount Gabriel near Schull.

Ignore a lesser road down to the right just after a ruin, and then after another uphill your road soon begins a winding descent and swings left. Ignore for now a T-junction, and continue down 300m along a leafy lane to the pier at Bulloch Island. The narrow rapids out of and into Lough Hyne are over to your left, but are difficult to get at. When ready, go back up to that last T-junction, and now you turn right, to return on a lovely level walk to the start, beside beech, holly, whitethorn and woodbine.

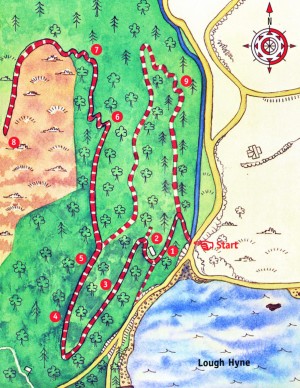

Knockomagh Hill Nature Traill

Follow the Nature Trail up Knockomagh Hill, overlooking Lough Hyne, for a spectacular walk (approx. one hour) with wonderful views of West Cork. The trail zigzags up to the summit of knockomagh Hill from sea level and back again to the start point. There are nine stops along the way. The total length of the trail is 2km but there is an opportunity to shorten the walk and avoid some of the steepest climbing by taking the northern loop at Stop 5.

Starting Point: The trees just inside the entrnce gate are mostly Sitka spruce, together with some fir species. These non-native species were planted in the 1950s as a commercial crop. Sitka spruce, which gets its name from the Sitka area of Alaska, was first introduced in Ireland in the 1850s. It has becom the dominant species of Ireland’s commercial forestry plantations and is favoured because it is quick growing and produces straight tumber, ideal for the construction industry. As the Sitka spruce mature in Knockomagh Wood, the trees will be harvested on a phased basis and the area will be managed to restore native woodland habitat to the area. The small stream on your right is one of only a small number of freshwater streams flowing into the marine waters of Lough Hyne. Otters, which feed in the lough on fish, crabs and other marine animals, use this stream to rinse the seawater from their fur. Their droppings, known as spraints, which consist mostly of undigested fishbone, can sometimes be found along the edge of this stream.

Stop 1: The Sessile Oak Sessile Oaks, which you can see around you, are the dominant species of most woodlands in the west of Ireland. Of all the native trees, oak supports the widest variety of insect life which in turn supports a range of birds, bats and other species of insect-eating animals. Over 200 species of insect inhabit oaks, in addition to nearly 20 species of bird. The number of insect species associated with a particular tree species reflects the abundance of that species in recent geographical time, particularly since the last Ice Age. Native species of tree have more insect species associated with them than introduced trees because the invertebrate life has evolved with the tree over a longer period of time. Behind you, and scattered throughout the woodland is a yew (Taxus baccata). Yew is one of only three native Irish conifer species, the others being juniper and Scot’s pine. The needle-like leaves of the yew contain toxins that can be fatal when eaten by domestic animals. Yew trees are either male or female and it is only the female trees which produce the poisonous red berries. However, the red flesh of the berries is particularly favoured as a food source by thrushes and blackbirds. While the central seeds are highly poisonous, these pass quickly through the digestive tract of birds without being crushed or digested. The high tensile strength of yew wood made it a favourable timber in the past for longbows and today this durable timber is in great demand by the makers of fine furniture.

Stop 2: McCarthy’s Cottage Here are the runins of an old cottage which was inhabited in past times by a Mr McCarthy who held the post of Wood Ranger for the local estate belonging to Henry Becher. Note the yew tree growing in the remains of the lean-to building. Evidence of the old garden is indicated by the presence of the very old laurel. Laurel is an introduced shrub and can become invasive under certain conditions forming a dense shrub layer which shades out not only the ground layer but also prevents regeneration of the canopy species thus having a detrimental effect on the whole ecology of the woodlands. Fortunately, laurel is not spreading in this woodland. At the end of the pathway to the left of the house is the spring which provided a convenient source of water for the McCarthy family. Heading up the slope towards the next stop you will notice the difference in the ground layer vegetation on each side of the path. Few plants are growing beneath the beech on the left compared to the other broadleaf trees on the right. Beech, a non-native broadleaf, blocks out much more light than native Irish woodland tree species such as oak and ash. This lack of light prevents plants growing beneath beech.

Stop 3: The Lough Hyne Panorama This stop affords a fine view of Lugh Hyne. The lough is divided into northern and southern basins by Castle Island. On the eastern side of the island (the left hand side as you look at it) you can see the ruins of Cloughan Castle. This O’Driscoll clan castle, dating from the 13th century , was built to protect the entrance of the lough from enemies approaching from the sea. Looking at the ground layer here you can see a variety of plant species which are adapted to woodland shade. For example, lesser celandine produces its yellow flower in early spring before the tall trees above open their leaves and block out the light. Note the disc shaped leaves of the pennywort on the stone walls of the seat. This is one of a number of plants known as coinneal Mhuire (Mary’s candle) in irish. The others include foxglove and mullein. The large ferns seen here are predominantly male fern and lady fern. The smaller ferns, typical of acid woodlands, include hard fern and Har’s tongue fern.

Stop 4: The Bluebell Glade This area has been opened up over time by trees being blown down by the wind. This openess has permitted the growth of a lush carpet of bluebells, which is best seen in springtime. To visitors from central Europe, bluebell woods are an eye-opener as the species is essentially an ‘Atlantic’ one and is not found further east than Western Germany. It is also absent from Scandinavia. Other plants seen here are wood-rush and herb robert. In time the tree canopy will close over this area again as natural regeneration of seedlings from adjacent trees replace the windblown ones.

Stop 5: The Fallen Beech This beech tree has fallen over some time ago but part of the root system has remained intact and the tree continues to grow, with one of the branches now becoming the main stem. Like most of the trees in this woodland, the beech trees have many polypody ferns and mosses growing on their branches and trunks. These are known as epiphytes –plants that grow on other plants but take no sustenance from the host plant, merely using the host plant to get closer to the light. Knockomagh Wood, in common with other relatively warm, moist, Atlantic woodlands in the south-west of Ireland, is a particularly good place to observe these epiphytes, which get their nutrrients from the rain running down the branches. However, just a few dry days in a row are enough to make them start to shrivel. How do they look today? Just ahead is a stack of felled logs which form part of the ‘deadwood’ component of the ground layer. Eventually the log-pile will decay and all traces of it will disappear as a result of the actions of fungi, bacteria and a range of small animals such as millipedes, woodlice and beetles, collectively known as nature’s recyclers. It is only when the logs have completely rotted that nutrients are released and can be used again by other plants. Rotting wood is therefore a very important part of the forest ecosystem, with many invertebrates depending on it for their sustenance. In turn, these invertebrates are eaten by larger insects, birds and mamals so that the nutrients are passed along the food chain, keeping the woodland wildlife alive. At this point you can choose to return to the entrance via the north loop or continue to the top of Knockomagh Hill. The view from the top on a fine day will more than reward the effort of getting there.

Stop 6: The Canopy View One of the interesting features of this woodland is that from here, you can get a bird’s eye view of the canopy layer of the woodland. As well as the oak, you can see other native broadleaf species such as hazel. On your right, the holly is a major component of the shrub layer. Holly is one of the plants, like yew, that has made its male and female flowers on separate plants. Only the female plants develop the familiar red berries. From August onwards you can see the green unripe berries which will ripen and fall as the autumn and winter progresses. Members of the thrush family, in particular the mistle thrush, the largest of the thrush family in Ireland, favour a feed of holly berries. In fact, individual mistle thrushes will often protect a particular holly bush, driving off any other thrushes who might try to feed from that bush.

Stop 7: St Patrick’s Cabbage On the rocks to the right of the steps is a clump of St Patrick’s cabbage. The garden plant ‘London Pride’ is a hybrid of St Patrick’s cabbage and another member of the saxifridge family. St Patrick’s cabbage is one of a small number of plants whose centre of distribution is in northern Spain and Portugal but who also have a limited distribution in the south-west of Ireland. These plants are known as ‘Lusitanian plants’ and derive their name from that area of Europe known as Lusitania by the Romans. Other plants of this group found in the south-west include the Irish spurge and the large-flowered butterwort, an insectivorous plant, found on bogs.

Stop 8: The West Cork Coastline This hilltop (197m above sea-level) affords a panoramic view of the West Cork coastline. You can see Mount Gabriel to the north-west and the islands of Roaringwater Bay including Sherkin and Cape Clear to the west. To the east you can see along the coast towards Galley Head. The Stags Rocks, to the south-east, was the site of the shipwreck of the ore carrier ‘Kowloon Bridge’. It ran aground in 1986, resulting in extensive oil spills along much of this coast. Fortunately the delicate ecology of Lough Hyne was protected by the erection of booms which were highly successful in preventing the entry of any oil into the Lough. The wreck is now a very popular scuba diving site. There are remains of signal towers at Toe Head to the east and Spain Point to the west. These were part of a network of signal towers from Cork Harbour to Dursey Island (at the end of the Beara Peninsula). They were built in the early years of the 19th century by the British military as part of an early warning system in case of another attempt by the French to invade. In December 1796, a French invasion fleet had sailed into Bantry Bay and it was only an unseasonable easterly gale which had prevented the French forces from landing. Using a combination of three flag designs and four balls hoisted in various arrangements, signals could be communicated between the towers and thus passed to military commanders stationed in Cork. The coastal heathland covering the ground here is typical of the ground vegetation of much of the headlands and islands of West Cork. It is dominated by ling heather, cross-leaved heath, bell heather and autumn gorse. The dominant conifer up here is lodgepole pine which shows many signs of exposure to the salty sea winds. This is the end of the trail. To return to the starting point, retrace your steps. If you want a change of scenery on your return, turn to your left at Stop 5 and follow the Northern Loop.

Stop 9: (North Loop) Here we have a small area of wet woodland with the native alder together with some planted Sitka spruce. The alder thrives in wet conditions and is often found along rivers and in waterlogged areas. Such soils are generally low in nitrogen compounds. However, in association with a soil borne bacterium, which is absorbed into root nodules, alder is able to fix atmospheric nitrogen. This is then built up into the organic compounds necessary for growth. Another indicator of the wet habitat here is the flag iris, so named because it was thought that the fluttering of the yellow flowers resembles flags blowing in the breeze. Continue along the track to return to the start of the trail.

Courtesy of National Parks & Wildlife Service