Seven Heads Walk

Situated on the picturesque West Cork coastline, the Seven Heads Peninsula extends from Timoleague village through Courtmacsherry, around the rugged cliffs and shoreline towards Dunworley Bay and on to Barryscove, Ardgehane and Ballinglanna.

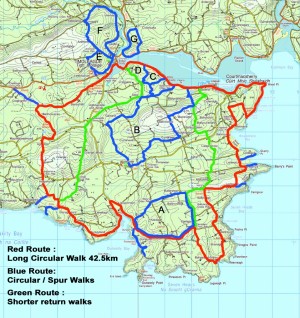

The walking route, which was launched in 1998, embraces a very interesting and varied territory with breathtaking and rugged scenery in the course of its entire distance of approx. 42.5km around the peninsula. As there are several return routes and circular walks one can choose a route to suit the time and energy available, as well as numerous side shoots or spur walks. There are also historical sites and a wide variety of interesting flora and fauna, which vary with the time of the year.

The walkway leads through a variety of different types of territory, rocky coastlines with magnificent marine life, sandy beaches, extensive rich farmland, picturesque villages and farmyards, prolific bird life with some rare birds such as the Choughs and the little Egret, old woodland and rows with fuchsia in abundance.

More importantly, there are friendly and chatty people to be met along the way. If you should find yourself unsure of the route, stop to chat, ask for directions and you will soon be on the right path. The development of the Seven Heads walk has been made possible by the tremendous support of the local communities of Barryroe, Courtmacsherry, and Timoleague, and especially the landowners who kindly gave permission to pass over their property.

Timoleague to Courtmacsherry

Distance: 3.2km

Starting from Timoleague — with its Franciscan Abbey founded in 1240 — take a left turn over the bridge at the signpost for Courtmacsherry. In the days when Bandon was a ‘mere waste bog and wood’ Timoleague had an important trade with Spain and France. Farm produce and hides were exported, and Mediterranean produce, in particular wine was imported. The schooners anchored near the Abbey before the harbour silted up after the great earthquake of Lisbon in 1750.

Follow the route of the Timoleague – Courtmacsherry light railway along the water’s edge. The mudflats on both sides of the causeway are a bird watchers paradise. At the corner is a sign with details of the railway and an attractive duck pond. Along the track, ceramic tiles give details of bird life, while picnic tables offer views of the Abbey and the scenic beech wood on the right of the road.

On the right, after one mile, is the ruin of the Cistercian Abbey of Abbeymahon. It was built about 1272 when the monks relocated from their original site at Aghmanister (The Monastery Field) in Spittal, founded in 1172.

In the days of the old steam trains it was possible to keep pace with the locomotive on a bicycle. Before its closure in 1960, The West Cork Railway was the last roadside railway in Europe. A Sunday excursion from Cork in the 1950s was a rare treat for the railway traveller. On entering Courtmacsherry you will see a grassed amenity park on the left. On the right is the Sacred Heart Catholic Church built in 1885. On the left, you pass a grassed picnic area with one of the Cardiff Hall’s anchors and a map of the Seven Heads peninsula near the old railway engine shed. On the right are brightly painted terraced houses and further along on the left you see the pier with its new yachting pontoon and lifeboat moored nearby.

Courtmacsherry is a beautiful mile long village, brightly painted, overlooking the sea and backed by a wooded hill. It is sheltered from prevailing southwesterly winds and has attracted visitors for generations. Once served by the West Cork Railway, which imported tourists and exported sugar beet and sea sand, its fishing and boat building industries made it a bustling centre in the early part of this century. Schooners discharged guano and coal at its busy quay and sailed for Dublin with cargoes of potatoes or fish. Courtmacsherry was founded by the Hodnetts, a Norman family who adopted the name Mac Sherry or son of Geoffrey and whose descendants still reside in the village.

Courtmacsherry, Wood Point, Ramsey Hill

Distance: 4km

From the pier in Courtmacsherry, walk eastwards along the street passing the small and lovely St. John the Evangelist Church of Ireland at the eastern end of the village. Walking eastwards, with the sea on the left, you pass the remains of an old pier by the lodge and Courtmacsherry Hotel on the right. This was once the summer residence of the ladies Boyle — descendants of Richard Boyle, Great Earl of Cork, an Elizabethan adventurer. His fourth son Francis, Viscount Shannon, had extensive lands in Courtmacsherry and Barryroe. A fifth son, Robert, was a famous scientist whose name is immortalised in ‘Boyle’s Law’. Once known as the Esplanade Hotel (comes from esplanade — a flat area for walking or driving by the sea), its grounds feature an ancient oak tree. The Gulf Stream influence on climate is obvious. Many Cordyline Palms flourish in its gardens, as they do elsewhere in the village. At the old boathouse on the left, turn right into an unsurfaced lane. Built in 1866, on land donated by the ladies Boyle, the boathouse housed Courtmacsherry Lifeboat in its earlier years of operation. Moving up the lane you come to an open field known as ‘the meadows’ and the path along its seaward margin that leads to Wood Point. The upper meadow has now been developed for housing, but the lower part remains intact. Ahead, the woods loom with towering sycamores and beech, while ancient oaks flourish on its seaward side. Enter by the gate and follow the well-worn path through the trees. In spring, the wood is carpeted with bluebells and wild garlic. In summer, the air is fragrant with the scent of wild woodbine. There is dense undergrowth of holly, ivy, briar and fern. There are paths to safe sandy bathing coves on the left. Some of the oaks have reached the end of their lives and are in decay, a clue to the wood’s age. Some have assumed fantastic shapes near the water’s edge. You will suddenly emerge from the sun-dappled gloom of the wood to a bright clearing. This is Wood Point or ‘The Point of the Wood’, which is a direct translation from the Irish Language, still spoken in these parts up to a hundred years ago. The waters of Courtmacsherry Bay sparkle to the east, with the Old Head of Kinsale marking its eastern boundary. To the north is Harbour View point, with Coolmain Strand and Castle, now owned by descendants of Walt Disney, the founder of the Disney entertainment and film empire. Turn southwards, past the beacon and skirt a number of grassy meadows that slope toward the sea and head for a stand of Sitka Spruce ahead. On the left are a number of fishing coves, including the ‘Frying Pan’, which may be accessed only by the very agile. Follow the existing path and cross electric fences by the wooden stiles provided. Treat electric fences with respect and remember sensitivity to electric shock varies enormously; what may be a tingle to you could be a nasty and painful ‘jolt’ to your friend. If you are quiet and lucky on entering the trees, you may see fox cubs and rabbits at play and if you remain until dusk, a badger or two. Emerging from the trees keep straight ahead. On the foreshore below and to your left are Beamish’s Cove and the remains of an old fort, now inaccessible from the land. On your left also is Broadstrand Bay and Coolbaun point. A whitethorn hedge now skirts the field. Ahead and to the left are the cliffs of File Na mBó. You now join up with the Fuchsia Walk, a miniature raised roadway once used by the ladies Boyle for access to the sea. Bounded by whitethorn on its windward side and Fuchsia on the sheltered side, it ranges from one to two metres in width. This takes you northwards towards Ramsey Hill. Emerge via a stone stile into a road. Turn left and continue to a T-junction. To continue the walk, turn left. Those who like a shorter walk, turn right and return to Courtmacsherry through the attractive hamlet of Ramsey Hill, with its small low houses once thatched and now tastefully renovated. The road is downhill and the walking easy. Be careful emerging on to the main road opposite the sign for Courtmacsherry. There is a blind bend on your left. Continue downwards past Kilkragie Lodge, taking care at the hairpin bend. This brings you back to your starting point. Covering these three miles at a leisurely pace takes about an hour and three-quarters. Starting at 11am, this walk will have you back in Courtmac for a drink and lunch at 1pm.

Ramsey Hill, Meelmane, Broadstrand, Barry’s Point

Distance: 3.2km

The starting point is Ramsey Hill. The road to the left passes Hill Top Cottage, descending towards Broadstrand Bay ahead. The Old Head of Kinsale and Garrettstown Wood are visible to the left. The road leads on past the Caravan Park on the left to Meelmane Village. This is a collection of eight low houses whose rooflines follow the fall of the road rather than the horizontal. This unique feature was probably a local solution to maintaining a thatch roof against the open southwesterly aspect. Angled thus, the roof threw off the wind rather than the wind throwing off the roof. In 1841, Meelmane (which means Middle Hill) had 954 people to the square mile. The road is now is a dead-end due to coastal erosion, but take a right at the second last double house on the left and enter an ancient hidden walkway between hedges of Fuchsia, Escalonia, Whitethorn and Blackthorn. Emerge via a stone wicket and cross two fields towards Broadstrand, which curves away to the left. The beach is sandy with shingle and rounded stones at highwater mark. With a spring tide and an easterly wind those stones can be heard ‘growling’, as far away as Butlerstown. It is a safe and clean bathing beach and is very sheltered in southwesterly winds. It offers excellent bass fishing and the odd run of mackerel in August adds to the fun. At the southern end cross a stream and walk for about 200 metres under the yellow clay cliff to where steps take you up to join the old road that once linked up with Meelmane Village before it was eroded by the relentless tide. Emerge on to the Lislee Court Road and continue southwards past a brightly painted cottage called Gull’s Nest. At the foot of the hill, the road swings left to the little fishing hamlet of Coolbaun and Blind Strand. Coolbaun was once densely populated and had a busy slate quarry. It was also the site of Lislee Castle, now gone without a trace. Ignore the left turn and continue straight ahead across two fields and up a steep cow path. The old stone wall on the right is part of the boundary of Lislee Court. Emerge on to the Barry’s Point road by an old stone stile under a sycamore tree. Rest a moment here after the climb and admire the view of Coolbaun, Blind Strand and the inner bay with Coolmain and Garrettstown strands in the distance. Turn left and walk towards Barry’s Point. As a small detour, walk eastwards. The flat silver sands of Blind Strand are on the left below. This sheltered strand had its sea wall shattered in a storm in December 1989. The road swings left and downhill after passing a farmhouse and shed on the left. Continue through a farmyard and pick up a grassy bohereen (little road) ahead. On the left is a small two-roomed house, with its roofline following the slope of the ground, as in Meelmane. It has one large and one small chimney. Dog roses mark what once was the back garden. Walking eastwards, old Lifeboat Station can be seen ahead on the left. This is now private property so be sensitive in your approach. The concrete and timber piles remain where they were cut off at ground level, the Jarrah wood retaining a faint red colour. On May 7, 1915, the lifeboat was launched from here to go to the aid of the Lusitania. Lack of wind hampered the rescue operation, which took three hours to row the 12-mile distance. It would take the Trent Class Lifeboat now in Courtmacsherry 20 minutes to complete the same journey. Timothy Keohane of Coolbaun, whose son Patrick went to within 150 miles of the South Pole during the 1910-12 Scott Expedition, was once a noted coxwain of the lifeboat. At this point you get a magnificent view of Courtmacsherry Bay. On the left is Coolbaun and Quarry Point with Broadstrand hidden behind them. You can pick out Wood Point and its beacon with Coolmain beach and castle in the background. The lane continues to a gate with a notice forbidding unauthorised entry. Any further progress would have to be in consultation with the landowner. But a word of caution: The tip of Barry’s Point has razor sharp rocks. It is as well left unexplored by the casual walker. Return by the same route and pick up an ancient bohereen on the left, 200 metres east of where you emerged into the Barry’s Point road.

Barry’s Point, Lackarour, Coolim, Narry’s Cross

Distance: 4km

Start at Barry’s Point. This pre-famine road brings you up the hill towards Lackarour. At first, the climb is steep but soon it swings to the right, running parallel to the road below. Here the walking is easier and the views even finer, including the tower of Lislee Temple Church on the right, a navigation mark for the harbour. The highest points on the peninsula, Barreragh and Ballincollop (140.5 m), are on the skyline to the right ahead. The lane opens into a field, swings left and uphill at the western corner and then right and westwards again, climbing at a shallow angle. From here, the high stonewalls of what once was Lislee Court Demesne can be seen far below. The lane, now wider, and in use for farming, loops around to the left before continuing towards the summit of the hill. At 106m, this is now the highest point of the southern part of the peninsula. Once over the summit the ocean comes into view and a magnificent vista opens up. From the Old Head of Kinsale to the left the horizon stretches away to the Galley Head a distance of 32km. One hundred and forty miles to the south east is Lands End, five hundred miles south La Coruna in northern Spain from where the Spaniards came to Kinsale in 1601 and three thousand miles to the southwest is Boston and New York, where so many Irish emigrants ended up after sailing from Queenstown. Below lies the Seven Heads Bay and Poulagh Nua Point with its hillside covered in Raitheanch or fern. Beyond is Cuas na Meagira point with the hamlet of Shanagh perched on the hill above. To the right, the Old Watch Tower on Travarra point marks the southern tip of the peninsula. Down in the valley to the right is the road that goes down to Trabeg or the small strand. Hidden on the left are the mighty Cliffs of Coolim, over 91m high. A few points east of south and twelve miles to sea marks the spot where on May 7, 1915 at 2.10pm Walter Schwieger launched a torpedo from his submarine U20, which sank the great British liner Lusitania with the loss of almost 1,200 lives. On that fine summer’s afternoon, school children in Butlerstown watched in awe, as the huge ship stood out on the water and vanished in under 18 minutes in a cloud of steam and smoke. Less noticeable on Thursday, April 11, 1912, at about 3pm, was the westward passage of a new White Star liner on her maiden voyage, after picking up 113 passengers at Queenstown. Three days later on Sunday, April 14, the Titanic grazed an iceberg and sank, taking 1,500 souls to a watery grave. When someone from the Seven Heads sailed on a liner for America, their friends lit a bonfire near the old watchtower as the ship passed. That rising column of smoke was the last glimpse many saw of the Seven Heads. Many never returned. You are now in Lackarour, which literally means ‘fat cheek’ and perfectly describes the rounded topography of the hillside. To make a short diversion to Coolim Cliffs, turn left and walk about 100 metres to where the road ends at a gate. Entering the field at the stile provided, walk along its seaward side inside the fencing. As you turn northeastwards the ground rises and you will find a vantage point where you can see the great cliffs and the sea far below. Don’t be tempted to venture outside the fencing. Men were once lowered by ropes to collect hawks eggs, which may account for the abandonment of the site by the hawks. A local legend of Coolim is preserved in the poem, The Maid of Coolim, written in 1874 by Heber Coghlan, a Church of Ireland schoolmaster in Lislee. In September 1642, the brutal Lord Forbes, returning to Kinsale after an attack on Clonakilty, was led astray by a drunken guide and instead of crossing at Timoleague found himself and his troops on the Seven Heads peninsula. A lovely local girl, Kate Barry, picking mussels by the seashore, was startled by the soldiers and rushed in panic towards the cliff pursued by a drunken soldier named Grimman. In desperation, she leaped over the edge, landing on a ledge of rock some way down. Grimman was not so lucky and plunged to his death. The spot was afterwards known as ‘Ladies Leap’ and no grass ever grew where her footprints had impacted. Returning from Coolim, retrace your steps past the lane where you intially emerged and proceed westwards passing three farmhouses on your left and taking in the fine views of Seven Heads Bay. Gradually the road rises and the ground on the left falls away. You now have a grandstand view of the southern half of the Seven Heads Peninsula. Away to the west, in line with the road if the air is clear, Mount Gabriel with its two Radomes (structural, weatherproof enclosures protecting microwave antenna) can be seen. This is a distance of 57 km, as the crow flies and is a good test of visibility. Best seen with binoculars, the domes gleam white in morning light and appear in silhouette in the evening. To the left, four separate headlands make up what appears as the Galley Head, the most prominent being Dunowen Head. In some conditions of evening light the four can be picked out with binoculars. Where the near shoreline drops away from the horizon to the left of Galley Head marks Dunworley Bay and the western boundary of Seven Heads. Here the tidal inlet to Grange bog is only 3.2km from the Timoleague inlet at Spittal Mill. To the left, where the land rises towards the horizon, the highest hump marks the site of a beacon erected after the sack of Baltimore in June 1631. Another was erected on Dundeady Head and one in Baltimore, which is still extant. In the event of an attack on Timoleague or Rosscarbery, the beacons were to be lit to warn the men of Barryroe to proceed to Clonakilty under arms. The pirates never came back and the beacon was never used. Further to the left a small dent in the shoreline is Foilareal Bay. The old watchtower stands out to the South. A fine old farmhouse, Mount Barry, is marked by its distinctive nine windows further to the left and completing the 180-degree turn you will see the Old Head of Kinsale behind you. Proceed westwards to Narry’s Cross. You now have several options. You are about 14.5km from your starting point in Timoleague and 3.2km from Travarra. To return to Courtmacsherry by Lislee, Ballincurrig and Meelmane is 5km, making a round trip of 19km. For this option, go to the right. Butlerstown with Mary and Dermot O’Neill’s pub and the Cardiff Hall Anchor is a half-mile straight ahead. To divert there for refreshments and return again to the walk will only add a mile overall. If you wish to continue towards Travarra, turn left and downhill towards Ballylangy.

Narry’s Cross, Ballylangy, Trabeg, Seven Heads Bay

Distance: 3.2km

Start at Narry’s Cross. There is no local name of Langy and the name may be an anglicisation of Baile Gleann Gaoithe or Townland of the Windy Glen. It is true that both westerly and easterly winds are funnelled along this valley, which runs the full width of the peninsula. From the Galley Head, the Old Head Lighthouse is visible through this valley with high ground to the north and south. You will glimpse the sea ahead on your left. On reaching Ballylangy Cross Roads, take a left turn and a 1km walk will bring you to Trabeg, a small sandy inlet once popular as a local bathing place. A grassy lane runs from the end of the tarred road. The descent to the beach is now only for the agile. It has a small cavern under a folded rock formation and at low water the beach measures 30 metres by 16 metres. Returning from Trabeg, continue down hill with Poulagh Nua visible on the fern clad hillside ahead. This is the outlet of a blowhole and the name suggests that it formed within living memory. Tradition holds that it was formed by a thunderbolt; given the explosion of compressed air that was the actual cause, this was a good description. On your right you should now see Ballylangy House amongst the trees. With its nine windows, it is a fine example of a prosperous landowners house. Built around 1690 and once the home of the Sealy family its garden has a stone wall 6m high, perhaps to protect it from the wind. At the foot of the hill, where a stream runs under the road, make a short diversion left to Seven Heads Bay. Here long fingers of rock jut into the sea. The rock has folded on edge revealing sedimentary layers of an ancient seabed. It has good mackerel fishing in August but use a strong line to avoid losing your gear in seaweed. On the right is a small shingle beach where the late Hurley brothers kept their rowboat and hauled their fish in homemade panniers up the steep ferny hill to their home in Ballinluig. The beach is now inaccessible.

Seven Heads Bay, Shanagh, Travarra, Butlerstown

Distance: 5.6km

Returning to where you diverted in the previous walk, you will now climb a steep hill to your left. On your right you will pass the fine old farmhouse called Mount Barry. James Redmond Barry was born here in 1789. A descendant of the De Barra Rua family, which gives the barony its name, this remarkable man was a benevolent landlord and social reformer in pre-famine Ireland. He was involved in linen production in Donaghmore and Clonakilty and later in fisheries and farming in Glandore. As the road climbs, the fences gradually change to dry stone walls reminiscent of Connemara. Pause at a grass triangle to rest and admire the view. On the hill to the north, the brightly painted houses of Butlerstown stand out. Narry’s Cross is on the skyline 1km to the east, with the bohereen where you emerged, to the right of the last white house. Further to the east is Barry’s Point and Carrig Rour rock. To the west, Dunworley Bay and Lehenagh point opens up. Walk southwards past the triangular field on your right towards a cluster of houses ahead. On your right is Ballinluig or the townland of the hollow. To your left you will see the outer part of Courtmacsherry Bay, Horse Rock, the Old Head and (with binoculars), Garretstown Beach. Soon, you will find yourself in a cluster of ancient houses. This is Shanagh, or to give it its full title Shanagh O Barravane. The houses and land belonged to the Earl of Shannon and the population was made up of small farmers and fisherman stock. There is an ancient burial ground nearby. Turn right into an old famine road and leave the village. You are now truly entering the hidden Ireland and the sense of timelessness, isolation and peace is awesome. The small fields are untouched by the green desert of intensive agriculture and still harbour many wild plants and flowers. The song of skylarks overhead announces that these quiet meadows are still a haven for wild life. Ahead on your right is located the old watchtower and coast guard huts. Built circa 1804, in anticipation of an invasion by Napoleanic forces, the tower was weather slated and had its clay mortar reinforced with a mixture of animal blood and hair. It is similar to towers on the Old Head, Galley Head and Toe Head. From any tower, at least two others are visible, enabling signalling by fire or flags between towers. Their survival in extreme conditions for almost 200 years is a tribute to their builders. A light was maintained on Travarra Tower until 1913. The coastguard huts were manned during both world wars. There was never any serious action on the coast and the small turf fire in the hut saw many card games and heard many yarns (stories) on a long winters night. The lane now swings right. Across a few fields on the left is a cove called the Roanseach, which is a breeding place for the roan or grey seal that is a familiar sight around the coast. During warm summer weather schools of porpoise and the odd dolphin may be seen, as well as basking sharks. Travarra inlet now becomes visible below on the left. Courtmacsherry Lifeboat was based here between 1874/75 but because of poor road access and exposed location it was returned to Courtmacsherry. On New Year’s Day, 1904, the French wooden sailing barque Faulconnier was wrecked here in a gale and fog. A local shore boat rescued the crew. Amongst the crew was a 16 year-old cabin boy. He ended his career as Harbour Master of Brest in France. In the early 1960s, his daughter disembarked from a liner in Cobh, visited Travarra and met the late Johnnie Whelton, the only surviving member of the shore boat crew. Both men were still hale and hearty at that time. Travarra’s most dramatic moment came on Wednesday, January 14, 1925 when its rocks and pools gleamed golden in the rising sun. The gold was maize and tragically it came at a cost of 28 lives; At 8pm the previous evening, the steamer Cardiff Hall hit the Shoonta Rock just to the east of the tower. She had perished in a raging gale after almost making it to Cork on a long voyage from Rosario on the River Plate in Argentina, with 6,000 tonnes of maize for Halls of Cork. For months afterwards Travarra was a hive of activity, as whole families worked to salvage the maize, which was dried and sold for feedstuff. The ship’s anchors may now be seen in Courtmacsherry and Butlerstown Villages. The road now peters out on the hillside, but just before, the path veers left, and follows the boundary of a field south-eastwards on the eastern shoulder of the inlet. On nearing the cliff edge it turns right towards the slipway. Here use the stiles into the field to avoid the coastal erosion. On warm days here the air is fragrant with the scent of fern and grasshoppers click in the rough grass. Step over the small stream that flows along the slipway and climb the meandering road on the other side. Butlerstown is glimpsed through a narrow glen on the right, two miles away. The village of Butlerstown owes its name to De Buitléir, a Norman family who were in Ibane before the De Barra family became dominant. The family gives its name to two more locations in Co. Cork, near Kinsale and Glanmire and there is also a Butlerstown in Co. Waterford. Butlerstown, on a hill overlooking the sea, is an attractive and colourful village. Its original low thatched houses were built with stone, quarried from the hill behind the houses. It once had five shops, three pubs, a post office, an RIC barrack and a church. It had three blacksmiths, two carpenter’s shops, stonemasons, a butcher, a bakery and a school. Patrick Keohane, who travelled almost to the South Pole with Scott’s expedition of 1910-12 was the most famous pupil of Butlerstown school.

Travarra to Carrigeen Cross

Distance: 1.7km

Leave Travarra and start climbing the narrow winding road uphill from the strand. This road was once busy with farmers harvesting seaweed. Before the advent of artificial fertiliser, seaweed and sea sand were very important to local agriculture. Cut with special hooks at low tide from a boat, or gathered after a storm, it was collected in heaps above high-water mark, and transported by horse and cart to the fields of Barryroe. In 1947, using sand and seaweed, Tim Donovan of Dunworley won the All-Ireland cup for sugar-beet production, achieving a yield of 17 tons per acre, after a spring marked by record snowfalls. Barryroe’s early potatoes also owed much to seaweed and sand. On reaching the top of the hill, you will view Butlerstown on the hillside directly ahead. This view was the last seen by many Butlerstown emigrants in the last century, as the great ocean liners from Queenstown sailed westwards past the Seven Heads. On your right, we can now see ‘The Glen’ that gives its name to the town land of Ballinluig (the town land of The Hollow). This glen separates Shanagh to the east, from Ballymacshoneen to the west. Ballinluig is reputed to have a mysterious hare only ever seen before the death of one of its residents. Walking northwards, on your left, just past the lane, is an old ring-fort. This area was once known as the ‘Faha’, meaning a flat grassy area fronting a fort. Ahead, the road swings left at a small cluster of houses. The first house on the left was, until quite recently, the last surviving thatched house in Barryroe.

Carrigeen Cross to Dunworley

Distance: 2.5km

Turn left now towards Dunworley. On the rocky land to your left can be seen one of the furze fields that were once a common feature of Barryroe. The furze shrub provided fodder for horses, nitrogen-rich fertiliser and wood for fuel on the open hearth. Its golden blossom can be seen all year round, but it is especially profuse in May. You will pass a cul-de-sac road on your left, which leads to the old signal tower on the cliffs. It is not advisable to walk on the cliffs, unless very familiar with the terrain. Further on, a road to the right leads to the ruins of a small pre-reformation church, Killsillagh or ‘The Church of the Willows’. The ancient parish of Killsillagh was one of the smallest parishes in Ireland (140 Hectares). On your left now is a large rock covered in furze and scrub. This is Carrigcluhur, or ‘The Sheltered Rock’. The road to the left winds around the base of the rock and leads, via a private lane to the right, to Foilareel, a small rocky inlet. The name Barry was once so prevalent here that the parish priest referred to them collectively as ‘All the Barry’s of Carrigcluhur’, in calling out the dues. Continue onwards and soon marshy reed beds on the left signal your arrival in Dunworley.

Dunworley Hill (Spur Walk)

Distance: 1km

At the road junction there is the option of taking a 1km cul-de-sac walk to the left to get a fine view of the bay from the top of the hill. As you walk to the left, notice the white house on your right, now private; this for many years was Dunworley Pub, where Sunday-afternoon trippers to the beach met for refreshments and often a sing-song before returning home. A lane on your right shows where the old road from Lehenagh, that ran by the edge of the ‘Back Strand’, emerged to join the existing road. Coastal erosion has removed all traces of the road. On your right ahead is the ‘Yellow Cove’, named after the colour of its cliffs. It was here that the Promontory Fort that gives us the name ‘The Fort of Hurley’ stood. Serious erosion here has been arrested by rock armour and access to the ‘Yellow Cove’ is now safe and easy. Around 1900, coloured beads were washed in here after the breaking open of an old sea chest from a wreck on Cow Rock in the bay. The beach next to the ‘Yellow Cove’, known as ‘The Foranes’ (pronounced Four-Awnes), has clean water and is safe from dangerous currents. At low tide, it has a gently sloping sand beach, ideal for bathing, swimming, or sunbathing. Climb the winding hill ahead and on reaching the summit you will be rewarded with a panoramic view of Dunworley Bay. To the far west are the Galley Head Lighthouse and Dunowen Head. Across the bay is Dunmore House with its golf course and golfers often clearly visible through binoculars. Further to the right is the entrance to Clonakilty Bay, seen over Lehenagh Point, which juts out towards Cow Rock, visible at low tide. Further to the right again, the houses of Lehenagh dot the hillside, and the inlet to Rock Castle can be seen. Through a v-shaped gap to the north, you should we see part of upper Carhue in Timoleague. Away on the far right, Butlerstown sits near the top of the hill. To the southwest runs the headland with the mound of the Peakin near its tip. Here stood the beacon erected after the ‘Sack of Baltimore’ by Algerian Corsairs in 1631. You can walk to the end of the road, but reaching the Peakin involves private land and is not recommended. The walk back is downhill and easy to Dunworley Bridge.

Dunworley to Barry’s Cove

Distance: 4.8km

Leave Dunworley Bridge and climb the hill, keeping left at the Y-junction. Below on your left is a small shingle beach and headland. A causeway once connected this to the slipway visible on the Lehenagh side. Inside the causeway was a marsh, running past Rock Castle and adjoining Grange Bog. The causeway was destroyed some time after 1842, and the marsh became flooded and eventually eroded. The sandy beach of the inlet has parts where the sand sinks underfoot, evidence of the boggy foundations of the beach. At very low tides, the stones from the shattered causeway can still be seen. The road meanders along the hillside, with the inlet on your left, and soon the walk is downhill, with the ruins of Rock Castle ahead on your left. This was once known as ‘Minister’s Hill’ after the Reverend Madras, who lived in the house beside the castle ruin. At low and medium tides, the beach here offers safe and pleasant bathing. However, do not try to cross to the Lehenagh shore, as there is a deep channel with fast currents in your path. Rock Castle is mysterious, in that very little is known of its history, or its unusual location. It may have been an early warning outpost for Timoleague, which was vulnerable to attack from Dunworley Beach. Walk on past the castle and houses, and keep left at the Y-junction, at the signpost for Lislevane. Soon you arrive on the causeway, bridging the outlet from Grange Bog. This road is liable to flooding at high tides. Before the construction of this causeway, mass goers from Lehenagh crossed near the pink farmhouse in trees to your right, and using an old lane, travelled cross-country to the church in Lislevane. This part of Lislevane was called ‘The Dawn’ in times past. Turf was cut in Grange Bog during the Second World War, but it contained a lot of salt, and the quality was poor. At the end of the causeway, swing left heading south again with the inlet on your left. This road offers the best view of Rock Castle and at low tide, a pleasant beach and estuary. The heron can be seen here, perched on one leg patiently waiting for a fish. The little egret, distinctive in his white plumage, joins him. The egrets now overwinter at Dunworley. On climbing the gentle hill, the road curves away to the right. As the road levels out, you have a fine view of Dunworley Bay, with its headland jutting out, topped by the Peakin, where once stood the beacon. As you walk downhill, Lehenagh slipway is on on your left. In the early years of the twentieth century, several local boats fished from here. Here also, and accessed by the slipway at low tide, is St. Anne’s Well. This was once a place of pilgrimage on July 26 — St. Anne’s feast day. At that time, the old road was on the seaward side of the well, before being destroyed by coastal erosion. A causeway and sluice gate controlled flooding of the marsh by Rock Castle. Near the well, a gold cup of Druidic origin was found in the 19th century. It is now in the British Museum. It was also an important watering place for sailing ships, and is marked as such on the charts. Local legend has it that German submariners watered here at night during WWl, around the time the Lusitania was sunk (1915). Walking westwards, the road gently climbs uphill. On your left now, you will see Bird Island coming into view behind the headland. As the name suggests, this is a nesting site for seabirds, safe from rats and land predators. At low water, the surf can be seen breaking on Cow Rock, and jutting out ahead, are Dunowen Head and The Galley Head Lighthouse. It was on Cow Rock, in 1701, that the slave ship ‘Amity’ was wrecked. The Amity belonged to the Royal African Company, and traded between between England, Gambia on Africa’s gold coast, and Barbados in The West Indies. Leaving England, with a cargo of brightly coloured ribbons and beads, these were traded for black slaves in Africa. Having sold the slaves in Barbados, they then returned with tobacco, rum and ivory tusks, and having sold these in England, started the cycle again. The capture of slaves was made easier by bribing a local chief, who provided captives from the local tribal wars common in Africa, in return for the brightly coloured junk beads. Only one black slave survived the wreck in February 1701, but for some reason, he never made it back to England to explain the wreck to the owners of The Royal African Company. The road progresses and curves to the right. On your left is the entrance to Clonakilty Bay and you can pick out Ballinglanna, Simon’s Cove and the houses on Inchydoney Island above The Lodge and Spa Hotel. Across the bay is Dunmore House. With binoculars, you can pick out the remains of the signal tower on Dunowen Head. Also visible are the wind turbines near Dunmanway, a sight becoming more familiar, as Ireland increases its use of wind energy. On progressing in a northwest direction, you will see a stepped pole beside a large cove on your left (Lion’s Cove). This was used as an anchorage for a cable, as the local coastal rescue team practiced rescue by Breeches Buoy. A lead weighted line was thrown across the cove. This was used to haul across the cable that supported the Breeches Buoy. Be warned! Stay away from the pole. There is a sheer and unguarded cliff just below it. It is no place for the casual walker. As you pass the cove, an old road opens to the right. This was once the main road and was known as ‘The Big Road’. As the road skirts the cove on yourleft, this is a place to keep children on a tight rein. You soon begin to travel downhill towards the inlet of Barry’s Cove. Ahead, near the skyline, the cottages and new houses on the ‘New Road’ from Ballinglanna can be seen. Barry’s Cove is a sheltered inlet, with a narrow entrance and calm, deep water inside. During the last century, it was a safe overnight anchorage for the lobster fishermen from Heir Island, who fished all along the south coast. They were known locally as ‘Baldi Boats’, but their correct description was ‘Towel Sail Yawls’. The three-man crew slept on straw beneath the tented foresail in the bow. They boiled potatoes and baked brown bread on a turf fire in a bed of stones at the bottom of the boat. They were renowned weather prophets and used up to a dozen indicators, including currents, wind, cloud formation, flight of seabirds, and the behaviour of the lobsters, to predict the weather. The local fishermen believed the cove was haunted and none of them would go near it at night.

Barry’s Cove to Y-junction

Distance: 0.5km

Walk on past Barry’s Cove’s group of houses towards Ballinglanna. On your right now, Barryroe parish church can be seen on the skyline. The road now swings to the left, by an old overgrown lane to the right, and proceeds up a small hill to a Y-junction.

Y-junction to Ardgehane

Distance: 1km

Back at the cul-de-sac sign, if you go to the right you will arrive at a small ruin by a field gate on the left. This is what remains of Donomore Church. The town land takes its name from ‘Big Church’. Before the opening of Barryroe Parish Church in 1871, there were churches at Donomore, Lislevane, Butlerstown and Lislee. As you move on, a road to the right gives a quiet leisurely walk through rolling farmland and traffic-free roads to The Grange Tavern, where you can enjoy some lunch. An alternative route to Timoleague can be taken via Grange Hill. Just ahead, turn left, and enter The Bóthair Nua. This was a famine project, to replace the old road destroyed by coastal erosion at Ballinglanna Strand. Around the turn of the twentieth century, a line of cottages was built along this road to rehouse people who lived in the small thatched houses of The Mall of Ballinglanna. In recent times, a number of new houses have joined them. On your right now, you should see the houses of Grange, the gorse, and forestry of Grange Glen, and in the distance, the fields and houses of Barryroe parish centre. As you move along ‘The New Road’, four field gates to the right, gives a panoramic view, with Barryroe Church to the centre, Butlerstown Hill to the southeast, and the heights of Barreragh to the northeast. Swing left now and the view to the west opens up.

Ballinglanna (Spur Walk)

Distance: 1.6km

A short walk down a steep hill affords fine views of Dunowen Head, Clonakilty Bay and Ballinglanna. It was only in the 1970s that the stream was bridged, enabling through-traffic. Up to then, one had to cross the strand, and ford the stream. The ruins of a small house, near the edge of the cliff on the left, mark what was the last thatched house in Ballinglanna. The strand once supported a small fishing fleet of about a dozen boats. Using long-line spillers, they fished as far as The Old Head, often selling in Kinsale. On a Friday morning, a line of donkey and carts climbed the steep hill, laden with fresh fish for the Clonakilty Market. There was great rivalry between Ballinglanna and South Ring for the pilotage of vessels landing at Ring Pier, often leading to a race to the incoming ship. Welsh miners explored a coal seam on the strand at the turn of the early 1900s, but it never developed into a mine. New holiday homes now replace the little thatched houses that lined the road running down to the sea.

Ardgehane to Main Road

Distance: 1km

Back at the signpost, turn right and walk northwards up a gentle hill. Wooden paling at a farm entrance on the left gives a fine view of the ocean and Dunowen Head. Walk onwards and you will soon reach the main Barryroe-Clonakilty road. Turn left on to this road. Walk on for about 50 metres and take a right turn, crossing the main road and entering a byroad.

Ardgehane to Aghafore

Distance: 2km

You are now on a byroad that links up with the lower Aghafore to Courtmacsherry road, which is about 2km further on over the hill. This was the site of a forge, which closed with the owner’s retirement in the late 60s. The blacksmith’s name was Dan Foley, a skilled craftsman renowned for his wrought iron work. Locals say he was the best at banding the timber-spoked wheels of horse carts with iron rims and newly fashioned wheels were brought here from near and far. Walk on up the slight gradient for about four hundred metres, passing a couple of houses on your left until the road levels out. Now stop and look around you. To the rear is the Atlantic Ocean stretching from the Old Head of Kinsale to the Galley Head and off to the west you can see Clonakilty bay. If the day is clear it is possible to see the peaks of the mountains on the Cork and Kerry border in the far off west, while if you look to the north east you may see the sun glinting off the shining fuselages of aircraft, as they glide in to land at Cork airport. The road you are now on was much used in olden days and was the shortest route the people of Ballinglanna and Ardgehane had to the old Clonakilty to Cork road. It is historic as well for another reason. During the famine times, records show that these two villages were decimated by fever and starvation with the result that almost half of the inhabitants died between the years 1841 to 1851. Some were buried in Ballintemple graveyard about two miles west of here near Ring village, but most of the victims were buried in their parish graveyard, which at that time was located at Cloughgriffin at the eastern side of the then parish of Templequinlan. The bodies were carried along this road by their grieving friends and relatives by whatever means they had at their disposal, perhaps some by donkey and cart, but most likely the majority by hand barrow. As you walk on, you may notice a laneway on your right. Nowadays this leads into a farmyard but up to about twenty years ago it also gave access to a large area of gorse and furze that covered the entire hill. Over the past two decades it has been reclaimed by the owners and is now pastureland. During and after the famine, families from Ardgehane and Ballinglanna were leased plots of this ground free of change by the landlord of the area and in return they cleared the scrub and bracken and cultivated the ground. Naturally enough, they planted potatoes and the seedbeds or ‘lazy beds’, as they called them, were visible as grassy ridges on the hillside up to recent times. Pause for a minute or two before you begin the descent down to the Aghafore road and look at the panoramic green countryside that stretches out before you. To your left, the tall water tower and extensive buildings of the Darrara Agricultural College dominate the countryside while in the wooded valley beneath concealed by the pine trees is the Catholic Church. Further west, you can see Clonakilty town nestling between two hills and off to your right is Timoleague bay with the ruins of the abbey clearly visible. Be careful walking down this stretch of road: It is not tarred and can be very rough especially after heavy rain. As you near the bottom of the hill the road improves and you pass an extensive farmyard on your left with a dwelling house on your right. You are now approaching the Aghafore road junction.

Aghafore junction to Chrois Dhearg junction

Distance: 0.5km

Take a right turn here and continue walking. This road can take you back to Courtmacsherry almost in a direct line passing through Aghawadda crossroads. However, you will only walk five hundred metres in this direction and then take the first left.

Chrois Dhearg junction to Ballincourcey junction

Distance: 2km

The left turn here is very sharp and cannot be negotiated by vehicular traffic from this side. This problem doesn’t concern you on this walk; you should have no trouble rounding the bend. The name Chrois Dhearg is unusual to say the least since its English translation literally means ‘Red Cross’ — so called according to local legend because in olden times at certain times of the year, as dusk began to fall, a large black dog with eyes gleaming like red coals emerged from this road and stood at this junction for a period of time ‘so that neither man nor beast could pass’. If you believe this to be true then the obvious lesson to be learned here is not to stay out late on this road. You are now on a byroad with a tarred surface, which runs along the side of a glen known locally as the Carrigcannon. It is about 2km long, winding and twisting, uphill and downdale, quite narrow in places, but thankfully with very little traffic. Continue walking downhill and looking to your left you will see the Cruary River flowing down the valley from the west. During dry summers it may be reduced to a little babbling brook, but after periods of heavy rain, it can burst its banks and spread out to cover much of the valley floor. The little stone bridge at the bottom of this hill becomes submerged and it is advisable not to use this road if you see or suspect flooding after prolonged rainfall. After crossing the bridge, continue uphill and pass the two houses on your right. The first house is set back off the road about 30 metres or so and is of some historical importance. It is the ancestral home of the O’Donovan Astna family, whose most famous scion was Tadhg an Astna, leader of the United Irishmen in the 1798 rebellion in this part of the country. A battle took place between the British army and a group of rebels led by Tadhg at Shannonvale, near the village of Ballinascarthy, on June 19 in that year. This was the only rising that took place in the whole of Munster and Tadhg was killed in the battle and his body buried in Ballintemple cemetery near Ring Village. Continue on uphill after passing the two houses until you come to a sharp left turn. On your right there is an old stone building with a rusty corrugated iron roof. There is an iron gate at the side of the building that opens into the field. Stand at the gate and look across the valley to the east. You will see a clump of rock and furze shrub in a large green field with a farmhouse a couple of hundred metres to the rear of it. This is the site of a cillín or a children’s burial ground and it has been much reduced in area over the years by cultivation of the field and the gathering of rocks and stones into heaps. By a coincidence, if you walk on another 50 metres or so, immediately inside the high fence on your left, you will find another burial ground. It is overgrown with briars and furze bushes but the slabs of long stone and rocks can be seen if you go exploring. Be careful if there are cattle in the field, they are usually more inquisitive than dangerous and make sure to close the gates after you. There is a story in the locality that in the penal times, a priest was being hunted by the Redcoats (British soldiers on horseback), and was fleeing along this road after coming from the southern parish of Barryroe. He was spotted by one of the soldiers who galloped his horse in his direction to cut him off. As the horse was jumping the fence in front of the priest, the soldier was thrown from the saddle and on to the road and killed. The actual spot where this happened is said to be midway between the corner immediately after the old burial ground and the following corner. Continue on your way for another few hundred yards, and now before you and off to your left, you will see Cruary bog, or more accurately what remains of it. It once covered over 243 hectares and extended westwards towards Darrara Church. However, because of reclamation, it is now only one quarter of its original area. This bog is the source of the Cruary River, which flows eastwards towards Aghafore and Aghawadda and flows into the sea at Spittal. It is interesting to note that further downstream towards Aghawadda, a dam was created, so that when the water was released, it aided the large water wheels in turning the grinding stones of the corn mills at Spittal. A splendid example of a retaining wall can be seen near the Aghawadda crossroads, built well over two hundred years ago and still in near perfect condition. Even though much reduced in size, the bog and surrounding marshland supports a variety of wild life. Wild duck, heron, snipe and moorhen are a common sight while pheasant and woodcock occupy the drier ground and in summertime this country road is ablaze with colour. Blackthorn and whitethorn bushes along with fuchsia and furze proliferate in the ditches and hedgerows. The scent of honeysuckle fills the air attracting many different species of butterfly to its flowers with the red admiral, tortoise-shell and meadow browns being the most common. Along the grassy dykes at the side of the road you will see a profusion of wild plants and flowers such as foxglove, purple dog-voilet and different types of fern or yellow ragwort interspersed along the way. As the end of summer approaches, the thorny briar with its humble fruit, the blackberry, comes into its own and there is always a bountiful harvest to be picked here. Before you begin to climb the last hill, look to the right and you will see an earthen ringfort about 60 metres in off the road. A stone fence runs from the fort down to the road with part of the fence having the appearance of the wall of a castle or similar structure. The ruins of Cloughgriffin Castle are in the next townland and in some written records it is also called Ballincoursig Castle. Since this is the townland of Ballincourcey (the place of Courcey) and there is evidence here of some fortification being in existence, it is most likely that there were two castles in existence with this one predating the Cloughgriffin castle. As you come over the brow of the last hill, the houses on the Ballincourcey road come into view. At the bottom of the hill is a 90-degree right turn. Just before you reach the corner, on your left side, there is a single concrete pillar near a gate. Measure back the road you came, some 15 metres from the pillar and on your left side search for what appears to be a gulley opening at road level. This is the entrance to what is believed to be a dugout or hideaway that was in use during the War of Independence. It measures about 5ft long by 2ft wide and 2ft high and may well have been used for storing weapons. Local tradition claims that this same dugout was used back in 1798 to store pike heads for the rebels, which is a plausible story since this area was in the centre of the leaders home territory. As you come to the end of this road, you will pass a house on your left on the approach to Ballincourcey junction.

Ballincourcey T-junction to Templequinlan graveyard

Distance: 0.7km

You have now reached the Ballincourcey (place of De Coursey) road so turn right to continue your journey to Timoleague. Before doing so, perhaps those of you with a little extra energy and time to spare might consider taking a left here and going on to Templequinlan church and graveyard. This road links up with the main Clonakilty to Timoleague road at Clashfluck crossroads, about half a mile further on, but the walk will not take you that far. About 100 metres after passing the first house on your left, you will see a double gate also on your left. Down in the field and about 100 metres away is what looks like a ringfort with a heap of stony rubble in one corner. This is all that remains of Cloughgriffin castle, built by the Normans probably in the 12th century. Very little is known about its history but its location would suggest that it may have some strategic importance since both Timoleague Castle and Rathbarry Castle could be seen from its ramparts. Continue your walk westwards for about 300 metres, passing a house on your right and another on your left, until you see the ruins of a church on your right hand side. The entrance is easily recognisable with two large stone pillars marking the entrance to a short laneway, which in turn leads to the ruined Templequinlan Church and graveyard. The church itself it reputed to be 7th century and the graveyard was at its busiest during the famine years from 1840 to 1850. Local people erected a memorial near the gable end of the church in 1997 to commemorate the many victims of this tragedy that are buried here. This hallowed ground was part of the former parish of Templequinlan, which stretched across country back to the coast and included the village of Ardgehane and surrounding hinterland. It’s known from written records that famine and disease reduced the population of this parish to almost half its original number and that a great many of those victims were buried here. Local folklore and stories of the terrible plight endured by the people still abound in this area, perhaps none more so than the misfortune to befall a family from the Ballinglanna area. The parents and all of their six children died and were brought here for burial by their relatives and friends. Being so weak and emaciated themselves, they were unable to dig the graves to the necessary depth, so they covered over and topped up both the parents grave and the children’s grave with stones from the wall of the church. Both graves can be seen at the southeastern side of the church still intact with their cover of stones At the northern gable end of the church there is a marked depression in the ground with what appears to be the remains of four pillars in a rectangular form. This is thought to be the site of a large burial vault of the Allen family, an English settler family who owned vast tracts of land in the area. Mention of this fact is made in The Topographical Dictionary of Ireland by Samuel Lewis published in 1837. When you leave Templequinlan, you must now retrace your footsteps back to Ballincourcey junction. About 50 metres on the way back, look to the left, you will see a tall white stone similar to a milestone embedded in the side of the ditch. Up to some years ago, markings, which resembled ogham writing were visible on the top of the stone, but unfortunately it has since been damaged by a mechanical hedge strimmer.

Ballincourcey to Barry’s Hall

Distance: 1.6km

Continue the walk in an easterly direction heading towards Timoleague. You will pass a number of houses at both sides of the road and then come to the brow of a hill. Before you start the descent, look to your left and over the fence and you will see a fine example of an earthen ringfort. These are the remains of an ancient dwelling, common in early Christian times. This one has got a deep trench or fosse round its perimeter, which may have been filled with water so that it created a defensive barrier against wild animals and intruders. For some unknown reason the townland of Ballincourcey and the neighbouring one of Barry’s Hall have each got several ringforts; perhaps it has something to do with the quality of the land since by any standards, the farmland here is exceptionally good. Before you move off the high point of this hill, look westwards and down the sloping green field. Towards the lower end, you will see part of a fence with a couple of furze bushes growing on it. This was the site of another ringfort. It had a souterrain or underground passage but unfortunately young cattle kept falling into it, so the owner decided to level the whole lot. Just across the valley, at the Aghafore side, there were two more ringforts and both have been demolished. However, in Barrys Hall there are two very good specimens still to be seen with both having the trench or fosse around them. As you walk on, you will pass a road on your right. This road exits about a mile further down at Aghawadda or as it is sometimes called Aghmanister crossroads.

Barry’s Hall to Ballinadroum junction

Distance: 3.2km

Just after this junction you will see a tarred road or laneway to your left. This is a cul-de-sac road down to two dwellings. A large sign in the corner of the field boldly proclaims that the Barry’s Hall herd of Holstein Friesians live here. On the roadside a few metres further on, there is an iron memorial cross with a copper inset, which tells us that a young man named Denis Hegarty (29) and a member of the volunteers in the War of Independence was killed by British forces near this spot on January 17, 1921. Continue walking along this quiet stretch of country road with acres of green pastures at each side of the fence. In this part of West Cork, the production of dairy milk is the most important agricultural activity and in this respect, the black and white friesian cow reigns supreme. In summertime, you can see them lying down with full stomachs, contentedly chewing the cud. This area is in the catchment area of Barryroe Co-op, which is consistently one of the top creameries in the whole country and supplies milk to the large Carbery Milk processing plant at Ballineen. To your left, across the valley, you can see the townlands of Carhue and Lettercollum, with the large period style residence of Lettercollum House dominating the hillside and being seen for miles around. This house has had a chequered history. Built originally by an English settler family, it was the home of the O’Hea family in later years. Eleanor, Lady Yarrow of London bought the house and the large quantity of land that surrounded it from Mr. Michael O’Hea. She had to return to London on health grounds some time later and it was bought by the Sisters of Mercy of Brisbane, Australia in 1937 and was used as a Novitate for some thirty years. The Land Commission acquired the land and house when the Sisters left. The lands were divided up among a number of small local landowners. The sports field, home of Argideen Rangers GAA club in Timoleague was also part of the original estate. You will pass another laneway on your right that leads down to a substantial dwelling and farmyard. John Good, who was suspected by the IRA of being a British army informer, owned it in 1921. He was shot and killed and his family subsequently fled the country. Next, there is a house on your left with another one on your right a little further on. You have now arrived at the top of Barry’s Hall hill. From here on it is downhill until you reach Ballinadroum and the edge of the sea about a mile away. At both sides of the road, as you go downhill, are tall sycamore and ash trees, with some beech and horse chestnut and laurel and prickly holly interspersed here and there. The branches lean across the road to greet each other and in summertime a dense green canopy of leaves blocks out much sunlight. Some time ago, before the advent of the Dutch Elm disease, there were many fine specimens of elm to be seen along this road but all have now disappeared save for the twisting sinewy remnants that have refused to die. On your right you will see the entrance and tree lined driveway up to Barry’s Hall House. This is the ‘Big House’ of the townland, a mansion built around the 1740s by one of the powerful Barry clan and after whom the townland is called. It was also occupied by the Deasy family of Clonakilty and Brewery fame, who moved here from Abbeyview House, which is in the adjoining townland of Aghmanister. If you look to your right down the expansive lawn to the front of the house you will see a number of standing stones or gullanes. Most of these stones were erected in pre-Christian Ireland and are said to denote the burial place of an important person. You will pass a dainty cottage on your left, which belongs to the ‘Big House’ and a large new house further down. After another 100 metres you will level ground again.

Lady’s Well (Spur Walk)

On the left, behind the trees at the side of the road, runs a small river, which enters the sea just beyond Ballinadroum junction. About a 100 metres before you come to the junction, a side road branches off to the left and joins up with the main Clonakilty—Timoleague road at Lady’s Well. This is a widely known holy well and is much frequented, especially on August 15. The holy well is situated in the townland of Lettercollum (in the Irish language this means ‘slope of the doves’) and tradition has it that a monk sat down to rest. He fell asleep and dreamt that a dove came to him with a letter. The letter told him to dig a well where he lay and that the water would help to cure lepers. The monk did this and cures were recorded. Walking sticks and crutches were left behind at the well. After visiting the well, retrace your footsteps back to the Barry’s Hall road and on to Ballinadroum.

Ballinadroum junction to Timoleague

Distance: 1km

You are now on the main Timoleague to Barryroe road and continue your walk to Timoleague. Ballinadroum means ‘place of the ridge or hump’ in the Irish language and this prominence begins here and continues round the corner towards Spittal. On our right is an inlet of Timoleague bay, which takes the shape of the letter ‘Y’ with its two forks branching off from its centre. You are at its most westerly point here at Ballinadroum and if you follow the channel around the green marshy island you will arrive at the most southerly point, which extends inland to Spittal bridge. Spittal Cross is located less than half a mile out the main road from here in the Barryroe direction and is now the site of an extensive pork factory adjacent to where the large corn mills ground flour for the surrounding towns and villages in the 18th and 19th centuries. You may recall the Cruary river was dammed upstream near Aghawadda to aid water volume for the mills, as was the Mill Pond, which was situated at the left side about 400 metres out the Barryroe road from Aghawadda cross. A plentiful and constant supply of water was needed to power the grinding stones and it is known from Lewis 1837 that Messrs Swete and Co ground 6000 barrels of wheat was ground here annually. The road here to the village is level and easy walking, but extra care is needed since there can be quite heavy traffic going both ways, especially on weekdays with articulated lorries being a particular hazard. On your left are tall silos and sheds; these are grain stores belonging to Barryroe Co Op. The original building was used as a flax mill. Flax was grown extensively in the locality over fifty years ago. On your right are the mudflats and grassy islands of the inner bay. Watch out for the pair of swans who made their home here several years ago and have since raised many a young cygnet. Curlews are in abundance here and are joined by flocks of plover and gulls and not forgetting ‘Judy the Bog’ (the heron) all gathering up the rich harvest of the sloblands. Ahead of you now is the village with its multicoloured houses, community centre, primary school and its very own landmark, the ruins of its famed Franciscan Abbey.

Bird life of the Seven Heads walk

By Peter Wolstenholme Courtmacsherry Estuary is designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and protected by the Wildlife Bill 1999 and European Habitat and Bird Directives. Walking through the village of Courtmacsherry, birdwatchers will spot Redshank, Greenshank, Bartail Godwits, Oystercatchers, the odd Heron and Swans. As you leave the village, with the estuary on your left, you will see the mud flats, which at low tide host up to 15,000 shore birds and wild fowl in the winter months. Arctic breeding birds start returning from late June onwards through the autumn. Many of these birds will carry on heading further south for the winter until October. The channel from the car park down past the wood is the best place in Ireland to see Great Northern Divers (Loons) which breed in the Canadian Arctic and spend the winter here. They are present from November through to May, diving mainly for shore crabs. They can be confused on the water with the Cormorant, another diving bird. The Cormorant jumps out of the water before it dives, whereas the Loon just puts its head under and dives smoothly. Courtmacsherry Woods is the only stretch of woodland on the walk and not notable for birds other than a few Blackbirds, Thrushes, Tits, Chaffinch and Robins. However, in April and May the woodland is carpeted from top to bottom in bluebells — a beautiful picture. Halfway through the woods are the ruins of the old village of Courtmacsherry — the only marker is the old water well and a few stone walls. A Robin always comes out to meet you at this point! On reaching the Point, leave the Wood silently and look down to the rocks — an otter is often seen fishing the inlets below. As you round the Point past the ‘Frying Pan’, where locals fill their bags with mackerel in the summertime, one or perhaps two Ravens will take to the air and watch your progress from a distance, for this is a territory they have held for a very long time. From December to July, on reaching File Na mBó at the end of Fuchsia Walk, Fulmars will be present, as they nest on the cliffs here. The Fulmar is one of the most successful birds of the 20th century. First found nesting in Mayo in 1911, it now nests around the whole of Ireland. These birds belong to the same family as the Albatross and this is the nearest you will get to a Wandering Albatross on this walk! Broadstrand is the main beach on the walk and because half of it is flat rock at low tide it is a wonderful microcosm of bird life. Of course, it is a favourite haunt of winkle pickers and the bay often holds massive shoals of herring and sprats in November, December and January. If this happens, a wildlife spectacle of Disney proportions will unfold before you. Up to 20 Grey Seals and 15,000 Gulls, Divers and Auks will feed on the bountiful harvest. If the tide is out, a fair selection of wading birds will be on the rocky shore, including the aptly named Turnstone, which lifts the seaweed and small pebbles to find its invertebrate prey. In summer, the Ringed Plover with its black and white collar, nests behind the beach — its well-camouflaged eggs are impossible to find. At the southern end of the beach, it’s possible that Mallard or Widgeon Ducks will leave the little marsh area. The next strand is Coolbaun. Note that the reed bed behind the beach will be your only chance on the walk to find Reed Buntings. Great Northern Divers always shelter inside Barry’s Point in the winter. The road at the top of the boreen has good hedges and a small copse of mature sycamore trees. This area in spring and autumn will be alive with Migratory Warblers, especially in an easterly wind, for it is one of the few places on the whole of the Seven Heads with shelter and feeding for insect-feeding birds. Up and over for Coolim; a little bird will flick its tail on top of a gorse bush and scolds you ‘chat, chat, chat’. This is the Stonechat you will meet on the walk. In the springtime look out for the rosy male Linnet singing along the boreens. Alas the Yellow Hammer, for so long a common bird everywhere, has declined severely over the last 20 years. Being seedeaters, they need mixed tillage farmland, so you are very lucky if you find one on this walk. They are still common inland in West Cork but not on the Seven Heads intensive dairy pastures. Normally nesting under the eaves of certain houses (bringing the occupiers bountiful good luck), House Martins also, surprisingly, nest at the top of Coolim Cliffs, where up-draughts bring them a constant supply of insects. As you walk along the high cliffs keep your eyes peeled overhead for the Peregrine Falcon who swoops on the Rock Pigeons…and according to pigeon fanciers, homing pigeons, who don’t make it home! During the winter, the Peregrine is much more likely to be found, along with its smaller cousin the Merlin, hunting over Courtmacsherry Estuary, where 15,000 birds have assembled for its pleasure. The hovering Kestrel is common along this coastline, and swooping down is just as likely to take a beetle as a mouse. Pride of place along this whole coastline goes to an agile Black Crow with a de-curved red bill and red legs; this is still the realm of the Chough (pronounced chuff!) This Cork and Kerry coastline is its last remaining stronghold in Europe. On Seven Heads, there are 10 to 20 breeding pairs out of a total Irish population of 300 to 400 pairs. Choughs have a strong preference for short grazed pasture where they can dig for food with their specialised bill. They feed on invertebrates, which are most abundant in undisturbed soils. The un-farmed coastal strip, with good caves for nesting sites, suits them down to the ground. In autumn, like all members of the crow family, they flock together and up to 40 birds can be seen together along the cliffs in September. They are unmissable, in the air with their buoyant flight, often with acrobatics, and calling their piercing slightly descending, ‘Chi-ah, Chi-ah’, repeatedly. On summer afternoons you could pass them unnoticed in a field of Rooks foraging in the grass, but as soon as they take to the air, you’ll hear their call. They are a symbol of the unspoiled Irish coastline, its undisturbed remoteness. The Corn Bunting was common around the old hamlet of Shannagh in the last century; its discordant metallic call heard around every farm in the land. Alas, this bird, whose last stronghold was the Aran Islands, became extinct in Ireland in 1998. Walking along the cliffs, a very fast flying pigeon will pass below and disappear into a cave. This is the now quite rare Rock Dove, from which all the city centre pigeons are descended. Its white rump distinguishes it from the Feral Pigeon. Up on the tops and over the open fields you will still hear the summer song of the Skylark, another farmland bird nearly extinct. If you hear one on a fine summers day, sit down and treasure the moment for free. In Germany recently, the song of a Skylark was advertised on a premium rate telephone line and 40,000 city dwellers paid a fortune to hear something from their childhood. All three large Gulls nest along the cliffs: The Herring Gull, the Lesser Black Backed and the Greater Black Backed. The Shag’s nests are located on low ledges near the water. This bird is a sort of more polite and dainty version of the greedy Cormorant, which nests on Bird Island at Dunworley. In winter, huge flocks of Starlings are to be seen across the open headlands, as well mixed Finches, mainly Linnets and Goldfinches. Also during winter, the fields will often resound to the hoarse call of a Pheasant at dusk. Snipe will often flush before you, zigzagging into the sky.